Shark Facts for Kids

With over 500 known species to date, sharks come in a variety of different shapes and sizes.

They have roamed the Earth’s seas for 400 million years, pre-dating dinosaurs by 200 million, and unlike many creatures, have remained almost completely unchanged.

Pick a type shark topic below, or click here for our general shark facts! 🦈

Latest Shark Facts

Hammerhead Shark Facts & Information

The shape of a hammerhead shark’s mallet like head also allows them to scan wider areas of the ocean floor in search of prey, acting almost like a radar.

Whale Shark Facts & Information

Did you know that the markings on a whale shark are unique to each individual, just like our fingerprints?

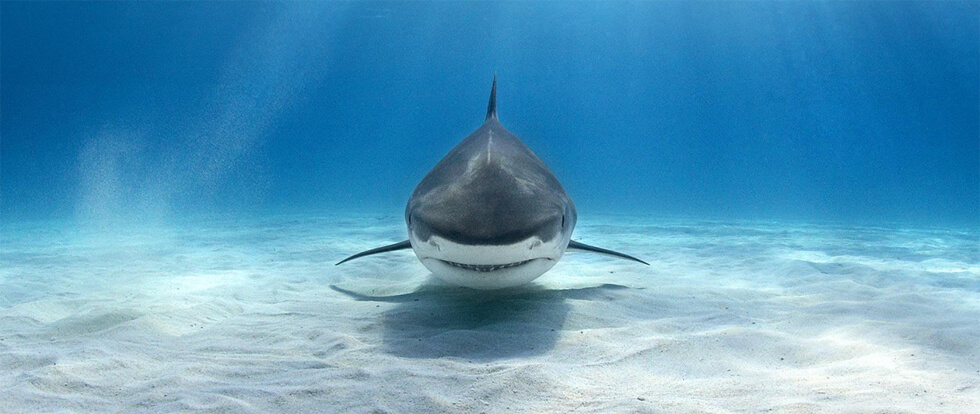

22 Jawsome Great White Shark Facts

The Great White Shark’s light grey upper body and all white lower half is known as ‘counter shading’, and helps when hiding from prey.

26 Bite-sized Shark Facts

5. Despite their negative portrayal in media and film, shark attacks are extremely rare. You’re more likely to be struck by lightning!

Shark Anatomy

If you ask someone to picture a shark, they’ll most like envisage their torpedo-like body shape, large distinctive dorsal fin and gaping tooth filled jaws. From the outside sharks may appear quite primitive, but despite being an ancient group of animals they are actually highly sophisticated. The general anatomy of sharks is fairly consistent across the different species, and the fact that they have remained unchanged for so long underlines just how effective their anatomical make-up is.

Unlike most fish that have just one gill, sharks boast five to seven gill slits on the sides of the head, and rely on a large oil filled liver for buoyancy as opposed to a gas-filled swim bladder. This liver takes up around 30% of their total body mass, and they use this in conjunction with forward movement to control vertical position.

Skeleton

Sharks belong to a family of fish known as Elasmobranchii, a subclass of Chondrichthyes, or in simple terms, cartilaginous fish. Chondrichthyes have skeletons made up of cartilage rather than bone, and lack a swim bladder. This particular class of fish contains over 600 species, including sharks, rays and skates.

Cartilage is lighter, more durable and more flexible than bone, contributing to Shark’s overall agility whilst also saving energy – vital when sharks must invest so much in constantly moving to prevent sinking.

Jaw

The jaws of sharks are not attached to their skull, instead moving separately with independent upper and lower jaws. This allows them to lift their head and thrust their mouth forward to bite it’s prey. While this varies among different species, most sharks have this ability to some degree.

Due to the sheer stress that this area of the shark is likely to experience, the surface of shark’s jaws have extra support in the form of tiny hexagonal plates called ‘tesserae’ – calcium salt deposits which give shark cartilage more strength. Often there is just one layer of tesserae, but larger sharks such as the great white shark have three or more layers.

Teeth

Sharks may have up to 3,000 teeth at one time and are fully embedded into the gums, as opposed to being directly affixed to the jaw. The shape and size of the teeth vary depending on their purpose, and there are four main types of shark teeth:

Needle-like teeth are typically found in sharks whose diet consist of small to medium sized fish, or even other small sharks. They are particular effective at gripping onto agile and slippery fish. Sand tiger tooth is pictured.

Serrated, wedge like teeth are found in larger species such as the great white shark (pictured), that feed on larger prey, and are effective at cutting off chunks of flesh for easy swallowing. The great white shark is a prime example of a specie with this feeding habit.

Dense, plate like teeth are used to crush the shells of prey like bivalves and crustaceans, and are found in smaller sharks such as the nurse or angel. Nurse shark tooth is pictured.

Teeth which serve no purpose at all are found in plankton feeders such as the basking and whale shark, who use their gills to filter feed. Whale shark tooth is pictured.

Fins and Tails

The majority of sharks have 8 rigid fins:

- A pair of pectoral fins that lift the shark as it swims

- One or two dorsal fins that offer stability

- A pair of pelvic fins that offer stability

- An anal fin that again, offers stability

- A caudal fin (tail) that propels the shark forward

The shark’s tail provides it’s forward motion, with speed and acceleration dependent on shape and size. Some tails boast large upper lobes for slow cruising with short and sudden bursts of speed, whereas others have larger lower lobes for continued pace.

Shark Diet

Most shark species are carnivorous, and no, humans are not on the menu. The gentle giants such as the whale and basking shark feed on plankton, filtering the water and trapping small organisms with sieve like filaments.

The range of prey is extremely broad, from small bivalves and crustaceans, to seals, birds and even other sharks. Generally sharks eat live prey, but have been known to feed on large whale carcasses.

Shark Habitat

Sharks exist in all seas, within a wide range of aquatic habitats and varying temperatures. They generally avoid fresh water, with the exception of the bull and river sharks that can swim between both sea and fresh water.

They are commonly found to a depth of 2,000 meters, with some existing even deeper. ‘Pelagic’ sharks such as the great white prefer large open waters, where as ‘benthic’ sharks such as the wobbegong are found skating along the ocean floor. Sharks are typically confined to their suited habitat for their entire lives, whereas some may migrate short distances or even entire oceans for the purpose of feeding or breeding.

Shark Behaviour

Many people will already have their own idea of the typical behaviour of a shark – a solitary creature roaming the seas in search of prey, attacking ferociously and instilling fear into those who dare venture into the ocean. This is predominantly due to negative media and movie portrayal, and is far from the truth.

Only a handful of species are solitary hunters, such as the great white shark, but even these species often coexist at active hunting or breeding grounds. Most execute a range of social behaviour, hunting in packs or congregating in large numbers.

Sharks typical cruise at an average speed of 8km per hour, as they need to keep moving in order to breathe. However, some shark species have adapted to benthic living, resting on the sea bed and actively pumping water over their gills. While we don’t know for sure, sharks never enter a true state of sleep. They do appear to have periods of inactivity, but their eyes remain open and even track the movements of their surroundings. However experiments have shown that some species are able to ‘sleep swim’, in which they are essentially unconscious while meandering around the ocean. This is possible due to the swimming being coordinated by their spinal cord as opposed to their brain.

Shark Senses

It’s often common knowledge that sharks are able to detect a drop of blood from miles and miles away, which is true to an extent. Their acute sense of smell is able to detect blood at one part per million, giving them the ability to determine the direction of a particular scent based on the time it takes to reach one nostril compared to the other. Unlike many mammals, the shark’s nostrils are used purely for smell as opposed to breathing, and are located on the underside of their snout.

As well as their keen olfactory senses, sharks also have great eyesight. A mirror like layer in the back of the eye called the tapetum lucidum (the same found in cats), doubles the intensity of incoming light and allowing them to see exceptionally well in dim conditions. While sharks do have eyelids, they do not blink, instead relying on surrounding water to clean their eyes. Some sharks boast tough membranes that slides over and protects the eyes while hunting or being attacked. Species that do not have this membrane instead roll their eyes backwards when striking prey.

While not as visibly present, sharks do have ears which are located within a small opening on each side of their head. Because sound travels faster in water, sharks rely on it heavily to alert them to prey or danger, and can detect sounds from over 800 feet away.

Sharks can also detect electricity, something which all living things emit, albeit in small amounts. This is due to the electroreceptors located within their snout, numbering in the hundreds to thousands. Sharks rely on this sensory organ, called the ampullae of Lorenzini, to pick up on small electromagnetic fields emitted by their prey, even detecting tiny creatures hidden beneath the sand.

Shark Reproduction

Most sharks live 20-30 years, maturing slowly and reaching a reproductive age anywhere from 12 to 15 years. While the majority of fish produce a large amount of small eggs, sharks are a k-selected species, which means they produce a small number of larger, more developed young. This results in a relatively high survival rate when compared to a large number of poorly developed young.

Mating between sharks is still rarely observed, especially between the larger species such as the great white.

Shark Fact-file

| Kingdom | Animalia |

| Phylum | Chordata |

| Class | Chondrichthyes |

| Subclass | Elasmobranchii |

| Scientific Name | Selachimorpha |

| Type | Fish |

| Diet | Carnivore |

| Size | 17cm (Spined Pygmy Shark) to 12 metres (Whale Shark) |

| Weight | 3lbs (Spined Pygmy Shark) to 13 tonnes (Whale Shark) |

| Speed | 5 km/h on average |

| Top Speed | 46 mp/h |

| Lifespan | 20-30 Years (In Wild) |

| Conservation Status | Threatened |